The Story of a Forgetten Musical Maverick

Text: Kevin Bazzana

|

|||

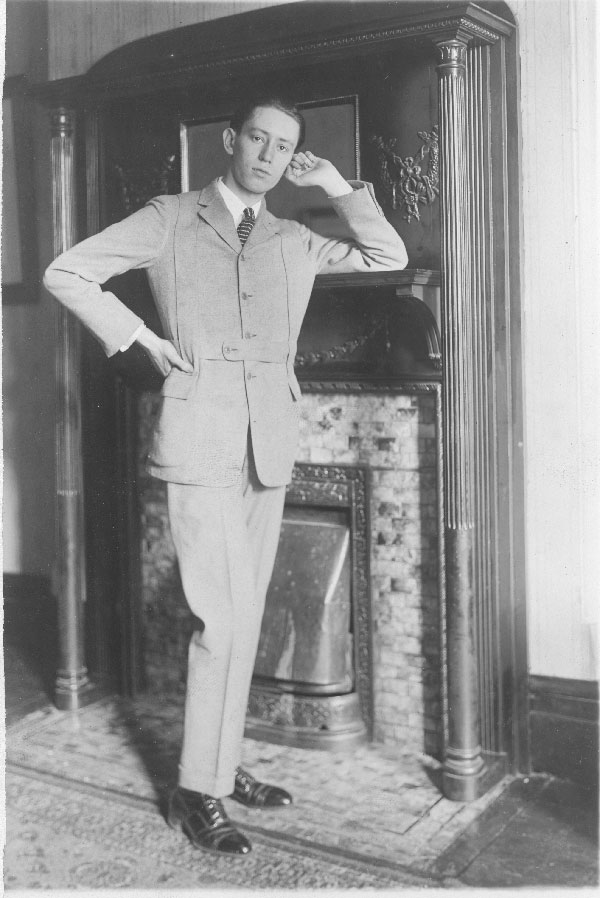

| Ervin Nyiregyházi (1923) | |||

Lost Genius is a biography of the Hungarian-American pianist and

composer Ervin Nyiregyházi. His name (pronounced “air-veen

nyeer-edge-hah-zee”) is little known today, except among

historical-piano buffs, yet the testimony of fellow-musicians, critics,

and other reliable witnesses, and of what documents and recordings

survive, reveals that he was one of the greatest and most idiosyncratic

performers of the twentieth century, as well as a prolific composer in

a strange, very personal idiom. Moreover, he was astonishingly

eccentric, and his bizarre life and personality would make for a

fascinating biography even had he not been an exceptional artist. (His

story has caught the interest of movie companies over the years—as

recently as the mid-1990s.) The book explores Nyiregyházi’s life and

art in detail, and makes a case for him as a geniune lost genius of

twentieth-century music.

Born in Budapest, in 1903, Ervin Nyiregyházi was one of the most

remarkable child prodigies in music history. In fact, a book devoted to

his gifts was published when he was just 13: The Psychology of a Music Prodigy, by Geza Révész.

(It remains a classic in the field of child psychology.) He studied at

the local academy of music, and word of his gifts spread quickly. His

parents exploited his talent, presenting him before countless local and

visiting aristocrats, intellectuals, businessmen, and cultural figures

(including composers like Lehár and Puccini and many of the great

performers of the day). At 6, he gave his first public recital; at 8,

he played for the nobility in London and for the royal family at Buckingham Palace.

Everywhere he earned praise and patronage, though being an idealistic

and strong-willed child he chafed against the prodigy life. Ultimately,

his anger at his parents’ exploitation and control, his shame of his

family’s lower-middle-class status, his experiences of anti-Semitism,

and his mother’s particular abuse all left lasting psychological scars.

During the First World War, he studied in Berlin (his piano teachers were Dohnányi and Lamond), and at 12 he made his concerto début with the Berlin Philharmonic.

In his teens, he gave concerts throughout central Europe, playing often

huge programs featuring the most difficult solo works and concertos, in

performances that amazed audiences, critics, and musicians.

In the fall of 1920, at 17, Nyiregyházi made a sensational New York début,

and for three seasons he attracted much publicity across America,

becoming a bona fide (albeit controversial) celebrity. His career was

poorly handled, however, and in 1924 he sued his manager; the case was

settled out of court (not to his advantage), but he was effectively

blacklisted in the music business.

Thrown onto his own resources,

he proved to be hopelessly incompetent at coping with day-to-day life.

He had been sheltered and infantilizd by his parents, to the point that

when he arrived in America

he still could not tie his own shoelaces or cut his own food (to the

delight of the tabloids). Soon he was destitute, sometimes going

without food and sleeping on the subway or a park bench. He was reduced

to playing in hotel orchestras, at Sing Sing prison, in private

recitals for gangsters, in concerts organized by the Hungarian

community—anywhere he could earn a little money.

|

|||

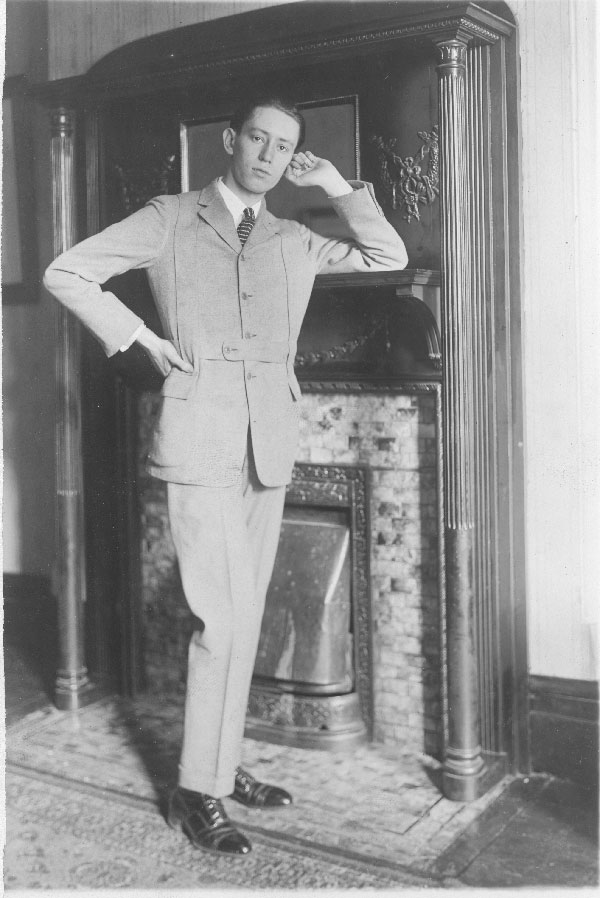

| Nyiregyházi as "Mr.X" | |||

In 1928,

with six dollars in his pocket, he relocated to Los Angeles, where he

did musical odd jobs for film studios. He performed in some early

talkies (Fashions in Love, The Lost Zeppelin,

Lummox) and performed or served as a “hand double” in piano sequences

in such later films as A Song to Remember, Song of Love, Soul of a Monster, and The Beast with Five Fingers(*).

Through the thirties and forties he remained in poverty, became a

drunkard, and spent most of his time composing, in an idiosyncratic

late-Romantic style. (He began composing at 3, and had written more

than a thousand works by the time he died.) He still performed,

sometimes with local W.P.A. orchestras, sometimes in private recitals.

Despite his low profile and poverty, his talent and personality won him

many fans. His circle of friends and admirers reads like a who’s who of

early-twentieth-century America: Rudolph Valentino and Harry Houdini,

Gloria Swanson and Bela Lugosi, Jack Dempsey and Theodore Dreiser, as

well as many leading musicians of the day. But he was a tormented and

self-destructive person, and despite the efforts of influential

persons, and occasional trips to New York and Europe, he could not

revive his career. With time, he became increasingly neurotic about

performing in public. In 1946, he agreed to give a recital in L.A. only

if permitted to appear disguised by a silk hood; he was advertised as “Mr. X—Masked Pianist.”

After the Second World War, his career as a pianist effectively ended.

He lived in cheap lodgings, drinking and composing; he did not own a

piano, did not practice, seemed unconcerned about the loss of his

concert career. He travelled often—to New York, to Texas and Mexico, to

Europe—sometimes in search of companionship, sometimes to relive better

times, sometimes simply because he was restless. He was voracious

sexually; his life was replete with long-term mistresses and

one-night-stands (many with married women), as well as prostitutes,

masseuses, and occasional male partners. He married ten times, rarely

successfully. One wife abused him, and their separation was fodder for

the tabloids (“SLAVE MAN BATTLES SUIT”). He divorced another wife

shortly after their wedding because she yawned during a concert;

another sought psychotherapy in Vienna with Freud; yet another was

deported for prostitution, and, out of spite, stole the book of essays

he had been compiling under the (characteristically grandiose) title

The Truth at Last.

|

|

In 1972, a group of historical-piano aficionados rediscovered Nyiregyházi, and he gave a few public concerts.

Word of his rediscovery spread, and in 1974 and 1978 he made some

recordings for the International Piano Archives. When they were

released, his unique and powerful piano style, and colourful

life-story, inspired a barrage of public and media interest:

interviews, newspaper and magazine articles, TV documentaries. There

were sensational headlines (“HOBO PIANIST REDISCOVERED IN TENDERLOIN”),

and much controversy among musicians and critics, but Nyiregyházi,

uncompromising when it came to his artistic ideals, was unwilling to

milk the publicity for the sake of money or status or fame. He refused

lucrative offers to play in in Carnegie Hall, and refused to abandon

his down-and-out lifestyle.

By 1980, the fad was over—except in Japan,

where he found a public that respected his artistic ideals. In 1980 and

1982, he gave concerts in Japan, where he was lionized, but he returned

to L.A., to the obscurity he seemed to prefer. He died there, of

cancer, in 1987.

His life reads like a

soap opera, but Nyiregyházi was no charlatan. Even after he dropped out

of the public eye, his playing could astonish the most informed ears.

The composer Arnold Schoenberg, after hearing him play privately in

1935, wrote (in a letter to Otto Klemperer) that Nyiregyházi was

“something utterly extraordinary,” a pianist of “incredible originality

and conviction” with an “astonishing” and “unparalleled” technique and

“power of expression I have never heard before.” “The sound he gets out

of the piano is unprecedented,” Schoenberg wrote. “I have never heard

such a pianist before.”

|

|

|

| Nyiregyházi Live series are available from Sonetto Classics official HP. Bazzana provides notes. |

Nyiregyházi made some Ampico piano rolls in the 1920s, but no recordings when he was in his prime. Still, the recordings he made in the 1970s,

despite his deteriorated technique, reveal a pianist with a rich

singing tone, an unparalleled dynamic range, a contrapuntal and

“orchestral” approach to texture, a very flexible sense of rhythm, and

(most controversially) a free, creative, improvisatory approach to

interpretation. He was a genuine Romantic adrift in the modern age;

even when he was a child, critics referred to his style as

“old-fashioned.” In fact, his playing was said to resemble that of

Liszt, according to former Liszt pupils who heard him play. He was a

ferociously individual artist—his heroes were Liszt and Wilde—and his

deeply personal musical interpretations scandalized many. Yet, he may

be considered a sort of “missing link” to a bygone species of

Romanticism that existed before the recording era. His eccentricities

and the faddish nature of his rediscovery notwithstanding, he was

musician of considerable historical importance.

*

Lost Genius

is the product of ten years’ research, and the story it tells has never

fully been told before, not even during the Nyiregyházi “renaissance”

of the 1970s. The book is based on archival material gathered from

institutions and individuals all over the world—most important,

Nyiregyházi’s own posthumous papers and those of his tenth and last

wife, who conducted hundreds of hours’ worth of interviews with him

covering every aspect of his life. The author also interviewed and

corresponded with almost all of the principal figures personally

connected with Nyiregyházi in the 1970s and 1980s, in the U.S., Japan,

and elsewhere, and with surviving family members in California. The

research received support from institutions directly associated with

Nyiregyházi, including his estate (the International Ervin Nyiregyházi

Foundation, in The Netherlands), the Takasaki Art Center College (in

Japan), the International Piano Archives at Maryland, and the Ford

Foundation (in New York).

First published by

McClelland & Stewart (Toronto) in February 2007, Lost Genius was is

due to be published in the U.S. by Carroll & Graf (New York) in the

fall of 2007.

Back to Fugue.us

Back to Nyiregyházi Top (Japanese version)

Back to Nyiregyházi Top (English version)

Back to Sonetto Classics